I’ve always wanted to travel and travel far – and now I long to climb on board a Cunard steamer more than ever. I want to go to New York! It seems that all the art of the world is there all of a sudden. Not the Mona Lisa and the Sistine Chapel, but the true essence of living, throbbing, jubilant art in the making. I do believe we live in important times. Young artists are transforming our aesthetics for good, even mine. Yes, good old Lavvie, admirer of Chowney and Seabrooke, suddenly feels that art has reached a point of no return: these young ‘uns will become the new classics in their lifetime, even if many dismisses them as a bunch of clowns making a joke out of beauty and all that.

So here is the news: the Armory Show, officially known as The International Exhibition of Modern Art, exploded the American art scene in a single night and the reverberations are to be sensed all over the world soon. It’s as if the shockwaves of the wildest European art went across the ocean to return a hundredfold amplified. Four thousand guests visited the rooms on the opening night. For the first time, the American public, the press, and the art world in general are exposed to the changes wrought by the great innovators in European art, from Cezanne to Picasso.

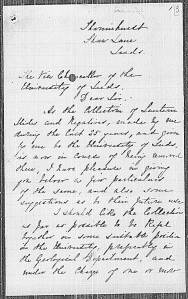

The first of its kind in the United States, the exhibit was the result of more than a year’s planning by a small group of artists, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS).

The AAPS abandons any obligation to realistic depiction, and as their realist predecessors have done, they cast aside allegiance to an academic ideal in favor of a newfound freedom. In their “modern” world, vision is not restricted to ideal forms, noble subject matter, harmony, decorum, and nature, but instead relied on an insightful, unfettered, soulful perception. They believe that the time has come to acquaint the general public with the vital new movements of modern art. And to stay true to their aims, these people put on an exhibition of giant proportions without any public funding whatsoever. That’s what we in England need: the bold entrepreneurial spirit of the true pioneers.

The major organizers were all names I’ve never heard of, but will remember now: American painters Walt Kuhn,Arthur B. Davies,Walter Pach. Overwhelming in its size, the exhibit includes examples of Symbolism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, and Cubism.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art

The exhibition seems vast! I can hardly imagine art on this scale, I first thought the paper had a type when I was reading the news: approximately 1250 paintings, sculptures, and decorative works by over 300 European and American artists. Separate rooms for for Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Cubists, Futurists, Symbolists, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Neo-Impressionists and other -ists from Europe and of course all the new art from across the United States. Among those European artists whose work was seen in the US for the first time were Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp. The American list of names looks so unfamiliar and exotic, it’ almost like another planet: George W. Bellows, Oscar Bluemner, Solon Borglum, Patrick H. Bruce, Mary Cassatt, Stuart Davis, James Earle Fraser, Childe Hassam, Edward Hopper, Elie Nadelman, Maurice Prendergast, John Sloan, Henry Twachtman, Bessie Vonnoh, and James Whistler.

Apparently the most scandalous work on display was Duchamp’s ‘Nude Descending the Staircase’, which is described by the New York Times critic as ‘an explosion in a shingle factory’. I’m yet to warm to Duchamp’s works, and I don’t particularly like or understand what’s going on in that painting (I’ve only seen a grainy photographic image), but I think I’m going to investigate once the magazines are restocked in the library. I need to understand this new idea of art!

In the meanwhile the home front is not too bleak either: The famous Parisian American who keeps the French art and literary world moving, a Gertrude Stein and her secretary are coming to London to find a publisher for her works over here.

She owns a great deal of modern art and some pieces of her collection have travelled to the Armory Show. But while what America did for art this year is colossal, I’m proud to say we were there first – even if at a much smaller scale. In fact, London’s Second Post-Impressionist art show had to close early, so that some of the paintings could be sent on to the Armory Show. I think this second show had a better reception from the average Brit than the first had back in 1910. Once the English have gotten used to Cezanne, they are more open to Matisse!

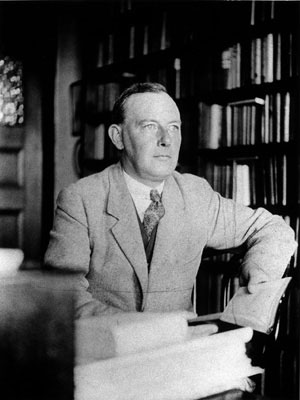

I feel that while we’re piddling with Cozens’ landscapes here, I have an awful lot of catching up to do about the crazy speed the art world is gathering. But when I feel that living in Leeds is like sitting on a horse-drawn cart while the steam engine of international art rushes by, I can always comfort myself with the thought that our very own Vice-Chancellor is aware of these movements and the future. No pressure, but if anyone, I expect him to respond to the latest art news with a good lecture or something, so that our youth would be aware of what’s happening beyond Barnsley…

Sources: AskArt, npr, Such Friends blog, and “1913: The Shape of Time”, Exhibition catalogue for the Henry Moore Institute (Essays on Sculpture, 66), 2012.

Lavender was right of course (helped by the pwer of hindsight) – the ‘lunatics’ and ‘clowns’ have indeed changed the landscape of art forever and became the new classics almost immediately. For example, the most talked-about painting in the 1913 Armory Show, Marcel Duchamp’s Cubist-inspired ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ depicting a human figure in abstract brown panels in overlapping motion sold for $324. After the commission, Duchamp received $240 — about $5,565, in today’s dollars. Not bad for an artist unknown in this country at the time.

Philadelphia Museum of Art/Copyright succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2013

Was it just the element of surprise? How sustainable was the shock effect? Duchamp in a 1963 interview he said that, at the time, artists had lost the ability to surprise the public:

“There’s a public to receive it today that did not exist then. Cubism was sort of forced upon the public to reject it. You know what I mean?” Duchamp said. “Instead, today, any new movement is almost accepted before it started. See, there’s no more element of shock anymore.

However, as Lavender might have felt too, it wasn’t just the element of surprise that mattered in the Arnory Show and the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London. While it certainly drew younger audiences, it was the inherent artistic value in these works that finally conquered the minds of the contemporary art consumer by breaking through the received sense of art as the representation of reality and a vehicle of aesthetics and beauty. Lavender is one of the many who began to feel that art is transforming to keep up with the challenges of modern life.”

No pressure, Vice-Chancellor Sadler!

(Michael Sadler, born in Barnsley, returned to Yorkshire in 1911 to take the post of Vice-Chancellor at the University of Leeds. By this time, he had already begun to develop the diverse artistic interests that would make him a notable figure in the history of modern art in Britain.

Sadler felt that a student’s education was greatly enhanced by a cultured and harmonious environment. He set about creating such an environment through the public display of pictures from his collection. He introduced a series of public events on a wide variety of topics, many arts-related, including talks on literature, daytime music recitals and a Saturday concert series. After leaving Leeds in 1923, Sadler served as Master of University College, Oxford, until 1934. The generous gift of artworks from his own collection, which he gave to the University in 1923, forms the basis of today’s University art collection, now on display at The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds.